Story by Jane Wrigglesworth, Photos: Sally Tagg, NZ Gardener

With the nearest city 90km away, the intrepid gardeners of Great Barrier Island tackle isolation with imagination and innovation.

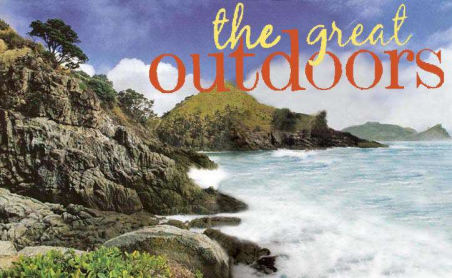

It’s gorgeous, it’s tropical, and it’s just a short flight northeast of Auckland, but until this year, I’d never journeyed to Great Barrier Island. I’d lugged my laptop to the furthest points north and south on our country’s map, but I’d never been across the sea to the Barrier. I can’t understand why.

With breathtaking, vast ocean views and glorious little holiday spots that hug the coast, the Barrier has all the hallmarks of a sun-drenched oasis in the Hauraki Gulf. Even the ocean presents itself as a simmering hotpot of fine seafood (our hosts at Le Soleil chalets and lodge dished up fresh crayfish and scallops, cooked on the barbie, for dinner!).

Photographer Sally Tagg and I were invited to visit the intrepid gardeners of Great Barrier in January. Getting there was easy. We simply hopped on a plane and were there in 35 minutes (although you can also take a ferry for a more leisurely cruise). It wasn’t until we arrived that the going got tough. Not in the sense of navigating the island—all 285 square kilometers—but in trying to fit everything in. There were so many gorgeous gardens, a cornucopia of home-grown food to eat, and myriad activities to do, that our unreasonably short visit didn’t do them all justice (who would have thought that sightseeing could be such hard work?).

Bananas, cherimoyas, avocados, sugar cane, and all manner of citrus, pip and stone-fruit trees, as well as an endless array of vegetables, graced so many of the gardens we visited that the underlying theme of island gardening is evident: self-sufficiency.

The Barrier has no reticulated mains power, water supply, or sewage system, and electricity is supplied by private generators or alternative power systems. You have to be both enterprising and adventurous to create a garden in this unique corner of New Zealand—and that’s exactly what they are.

Flax House

One man’s trash is another man’s treasure—or in Wayne McVicar’s case, art. This talented artist has a knack for turning discarded objects into works of art. “I like function, but I like compiling function with beauty.” He and partner Linda Power have turned their gorgeous clifftop home at Tryphena into a welcoming retreat filled with sculptures and artwork.

Wayne carves from stone, wood, and other natural materials and is always experimenting with nature. “I love piling up found objects into beautiful forms—which they were originally, anyway.” When she’s not teaching yoga, Linda tends their organic garden, and the couple is also developing gardens and an orchard on their nearby 22-hectare bush block. Fifteen years of collecting discarded fishing nets off local beaches has resulted in a colorful walkway.

Caity and Gerald Endt

I’m not sure I’d know a ‘Delicata’ squash from a ‘Musquee de Provence’ pumpkin, but the Endts do. Caity and Gerald Endt moved to the Barrier a couple of years ago to set up an organic market garden and orchard (Okiwi Passion) of honeydews, bananas, babaco, cherimoyas, watermelons, banana melons, acorn squash, passionfruit, corn, butternuts, buttercups, chilies, capsicums, beans, eggplants, salad greens, herbs, and edible flowers… the list goes on. Take one look at what Caity and Gerald are harvesting and eat your heart out. That’s if you’re lucky enough to live on the island.

The local cafés and stores are better off for it (they lap up the salad greens and edible flowers), but the Endts are struggling to keep up with demand. Next year they aim to double production. “We’re certainly not meeting café demands,” says Caity.

As a way of making space productive, the Endts interplant as much as they can. Passionfruit grows alongside garlic and babaco; bananas alongside tamarillos. “Within 18 months you have fruiting bananas, which gives the tamarillos part shade and a microclimate,” says Gerald.

All members of the Solanaceae family, including tomatoes, grow well here.

A beneficial insect strip (a Kings Seed mix) attracts and hosts predator insects, and cleome acts as a catch crop for green vege bugs (Caity picks off 20 a day to feed to their chooks!). Sunflowers are a great companion plant for cucurbits—they attract bees and bumblebees and eventually the green vegetable bug when they go to seed. The chickens roam in a large enclosure to catch bugs in the soil, including bronze beetle larvae which emerge from the soil from September to November.

But if it’s hands-on gardening experience you’re after, Caity is the person to call. She runs free horticultural courses on the island through NorthTec. But it’s more than just an invitation to have fun and learn new skills—it’s enabled her students to establish and tend a community garden as a vehicle for their learning. And the garden is a true delight.

PEST CONTROL

Last year Gerald and Caity grew a plot of watermelons, but come ripening time the rats beat them to them. This year they’re growing their watermelons, and cucumbers and celery, in an enclosure.

Native kaka are also a big problem for Great Barrier’s gardeners. They’re forced to net their fruit trees to keep the birds off (although this doesn’t always deter them—the crafty birds simply bounce on the netting until the fruit falls off the tree). Gerald places a dead rabbit on a high platform to attract hawks to deter kaka.

Sue and Bruno Reusser

When your office view flaunts emerald waters and sweeping vistas, you probably don’t mind going to work every day. Meet the happy couple Sue and Bruno Reusser, whose hand-crafting of home and garden has culminated in a picturesque haven.

Sue and Bruno have lived on the Barrier for 35 years. They built their home (using no power tools because they didn’t have a generator then; although they now have solar and wind power), then developed a lovely garden overlooking the estuary.

A savvy hotchpotch of veges and flowers grows side by side, and the emphasis is on organic gardening and self-sufficiency. They never spray: “Not even organic sprays.” They’re too busy being mussel farmers for that. Most veges are allowed to go to seed, for two reasons. Carrots and parsnips are particularly fine-looking in flower, says Sue, but they’re really there to attract the beneficial insects. And the whole outlook, with pretty flowers and seedheads, looks splendid indeed.

Hundreds of plants have been grown by seed that Sue has collected, and others from organic seed bought from Koanga Gardens and Kings Seeds. Sue experiments with new varieties regularly, particularly those that have a short growing season. ‘Hungarian Yellow Wax’ peppers—a hot, canary yellow, banana-type chili—have been a great success, as have the long thin Japanese eggplants. Certain varieties of tomato do well here, like ‘Russian Red,’ a variety that apparently does well in Dunedin too.

Climbing a gentle slope, you come to the house and orchard. The verandah is clothed in grape vines (I can vouch for the tastiness of the fruit!), and an adjoining area is home to several fruit trees. Wander a little further and there are still more fruit trees.

“It’s too warm to grow apricots and cherries and too cold to grow coconuts. But we can grow everything that’s subtropical. We have bananas—the ‘Lady Finger’ varieties, which grow better in a colder climate—cherimoya, casimiroa, nine different varieties of plum trees, figs, nine different types of apples, a dozen feijoas, quinces, pears, nectarine, guava, lots of citrus, macadamia nuts, and lots of peaches.” It’s a veritable fruit bowl.

FREE AS A BIRD

There are always plenty of eggs at the home of Bruno and Sue Reusser. The Reussers keep between 12-18 chickens in a large enclosure beside their orchard.

At mealtimes, they’re fed a diet of mussels and garden scraps, and each day they’re let out of their enclosure and allowed to roam freely around the orchard to scoff any bugs and fallen fruit—and to fertilize the ground. A system has also been set up in the chook house so that manure is easily collectable for the garden.

Sven Stellin

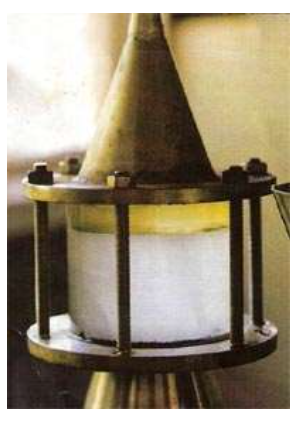

The pot was an old steel can with a bolted lid. The condenser was made of steel and aluminum piping, and the oil separator was a brandy bottle with holes drilled in to let water in and out.” So began Sven Stellin’s first attempt at extracting oil from kanuka and manuka.

Sven, who has lived on the Barrier since he was one, took over the running of his family’s farm at 19 when his father died. But farming wasn’t to be his destiny. He had, shall we say, more romantic plans: to extract the aroma from New Zealand’s tea tree oil. But it wasn’t until 1985 that his interest was rekindled by two things. One was the discovery of an article in a magazine, the other an accident that involved a local boy. “A wood splinter had penetrated the boy’s eyeball and it was a couple of days before he received medical help,” says Sven. “The local doctor removed the splinter and found there was no infection in the eye and it consequently healed very quickly. When asked why the eye had not become infected, the doctor said it was because it was a tea tree splinter and tea tree has known antibacterial properties.”

Coincidentally, the article in an Australian magazine described how bush stills were used to extract oil from natural stands of melaleuca, the Aussie tea tree. So Sven decided to give it a go with his homemade version. His first extractions failed miserably. “The oils extracted, but they came out a reddish, golden yellow colour (as opposed to pale yellow). That’s because a chemical reaction occurs when kanuka oil comes into contact with iron or steel.”

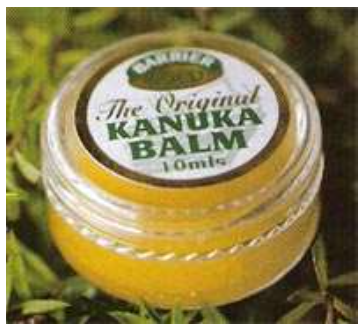

Sven continued to extract oil with his tiny still for his own use until he decided to turn his hobby into a commercial venture. He experimented with a much larger still, made his own products—balms, soaps, mozzie repellents, and essential oils—and Barrier Gold was born. (See www.barriergold.co.nz.)

Sven now runs tours and sells kanuka and manuka products from his shop on the premises. And if you ask nicely, he might take you for a ride on the back of his tractor to the topmost point of his land (I still have the bruises to prove it!). With 809ha and 43km of coastline, the views are spectacular.

Going to school was an adventure for Sven. It began with a three-mile boat trip up the FitzRoy harbour, then a three-mile trip by road down into the Okiwi Basin. Many school days were missed during winter.

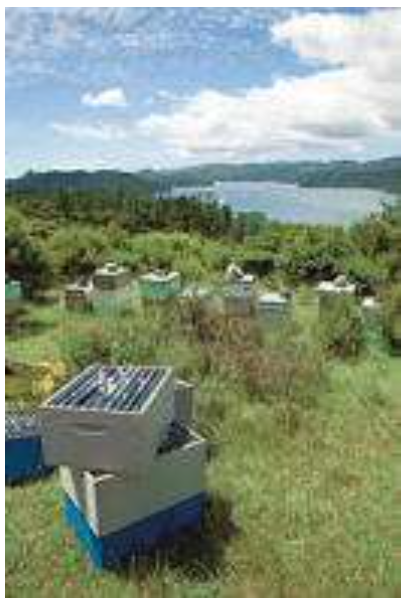

BEE FRIENDLY

A beneficial bug in a bud has got to be worth at least two in the bush, but a bee in a manuka bush is worth gold. Barrier Gold, that is. At the top of Sven Stellin’s property, a number of beehives keep the local bees abuzzing.

Local beekeepers tend the hives, which produce honey for Sven’s Barrier Gold brand of 100% pure manuka bush honey (it’s divine). Great Barrier Island honey is also used by the Great Barrier Island Bee Co. for their assortment of products (soaps, lotions, hand cream, lip balms, scrubs). Check out www.lesfloralies.co.nz for more details.

Les and Beverley Blackwell

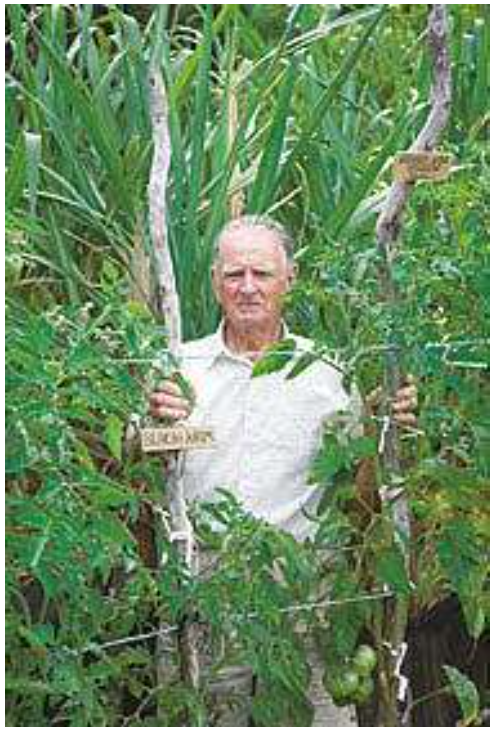

Les Blackwell’s heirloom tomatoes are sheltered by a thick hedge of sugar cane. The windbreak was grown from three canes. “Just lay them flat on the ground and they grow up from the joints,” he says.

Should you ever find yourself within shouting distance of Kaitoke Beach on Great Barrier Island, look out for Les and Bev Blackwell. I suggest courting favor with this engaging couple. You’ll likely go home with a bag of produce. From the roadside, though, you’d never guess there was a garden at all. But beyond the bush front, a magical arrangement of compartments (“they’re here, there, and everywhere”) make up this three-quarter acre (0.3ha) garden. And there’s no end to the list of crops Bev and Les grow: apples, pears, apricots, feijoas, plums, kiwifruit, citrus, guavas, peaches, persimmons, passionfruit, quinces, avocados, onions (there are 900 plants!), macadamias, heirloom tomatoes, numerous pumpkins and squash, corn, kumara, and NZ spinach.

Les also grows the sweet-flavored ‘Cupla’ squash, which his great uncle Adam Blackwell brought to New Zealand in the late 1800s. “We’ve had it in our family ever since. It grows into a circle, a three-quarter circle,” says Les. “And it has a flavor of its own,” adds Bev. “When it’s truly ripe, it’s an orangey colour. You cut it into rings and cook it. We either fry ours or roast them.”

Les and Bev’s family tree makes up part of the history of Great Barrier Island. Bev’s great-great-grandparents, the Sandersons, arrived on the Barrier in 1863, whereas the Blackwells (Les’ great-grandparents) arrived in 1867. Beekeeping was first started by George Blackwell (Les’s great-grandfather), and by the 1890s the island had over 1000 hives. In 1892, silver was discovered at Okupu by the Sandersons.

Wander around the Blackwells’ property today and you’re treated to delightful anecdotes of family history. Their plants, too, aren’t merely productive; each tells a story of the couple’s incredibly rich and adventurous life.

A ‘Red Haven’ peach has its own legend. “A branch fell off my mother’s tree,” says Les, “and took root. I dug it up and planted it here. I didn’t feed it. I didn’t do anything with it because peaches love sandy soil.” But it grew, and it grew well.

TASTY TUBERS

Les Blackwell grows several different varieties of Māori potato, most sourced from Koanga Gardens. Pictured above (clockwise from top left) are: ‘Paraketia’, ‘Urenika’, ‘Pawhero’, unknown variety, ‘Whataroa’ (Old Pink), a Maori lavender variety, ‘Karoro’ (aka ‘Old Yellow’), and ‘Kowiniwini’ (aka ‘Old Zebra’).

In winter, Les banks the area down with newspaper and cardboard and covers it with a mulch of lawn clippings and sugar cane. By planting time, the worms have munched it all down, and what’s left is a beautiful soil.

Reproduced with permission – Subject to copyright in its entirety. Neither the photos nor the text may be reproduced in any form of advertising, marketing, newspaper, brochure, leaflet, magazine, other websites, or on television without permission from NZ Gardener.