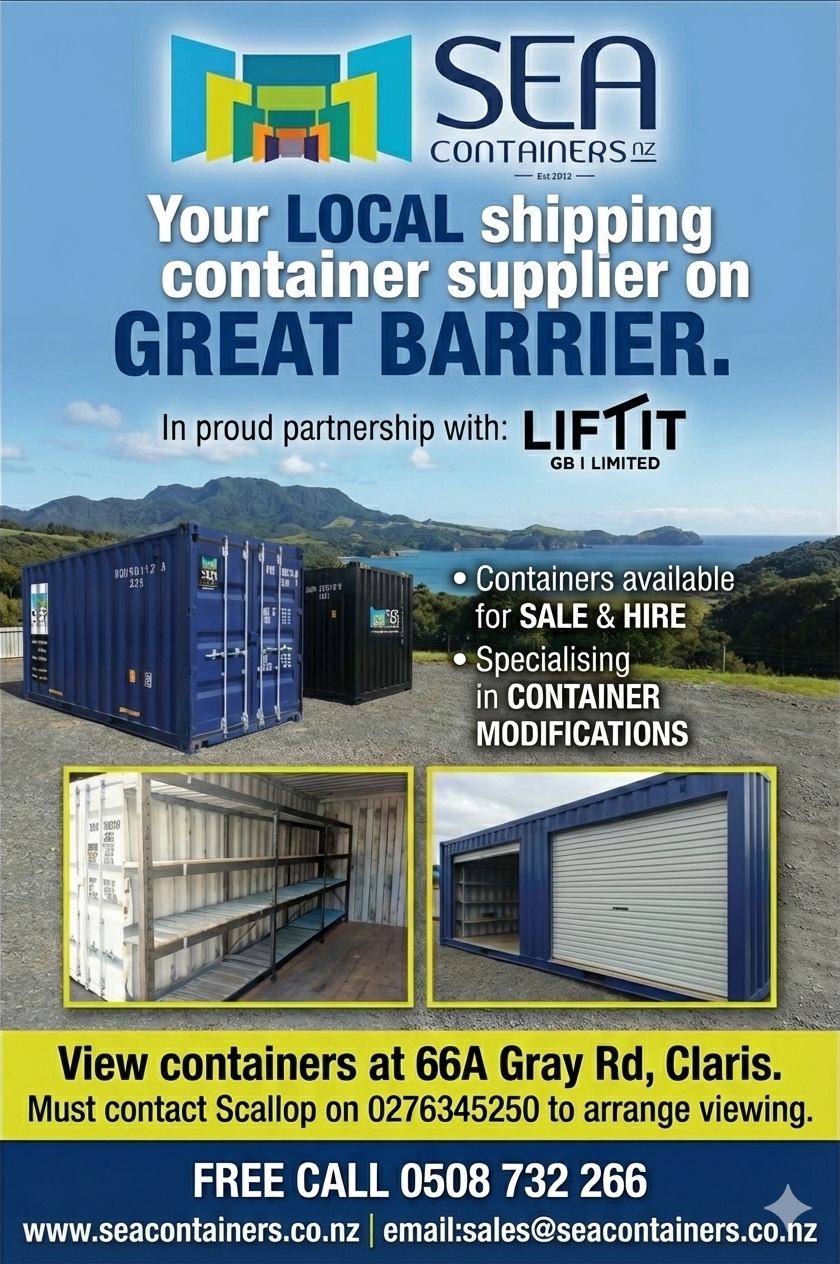

Photo / Lachlan Macnaughtan, CC BY-SA 4.0

By Brittany Finucci, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and Cassandra Rigby, James Cook University

The deep ocean, beyond 200 metres of depth, is the largest and one of the most complex environments on the planet. It covers 84% of the world’s ocean area and 98% of its volume – and it is home to a great diversity of species.

Yet it remains among the least studied places on Earth, with no comprehensive assessments of the state of deep-water biodiversity and no policy-relevant indicators to guide the taking of species targeted by fisheries.

This also applies specifically to deep-water sharks and rays, even though these species make up nearly half of the recognised diversity of all cartilaginous fishes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) we know today.

Our research highlights how our growing impact on the deep ocean raises the threat to these species.

Using the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species, we show that the number of threatened deep-water sharks and rays has more than doubled between 1980 and 2005, following the emergence and expansion of deep-water fishing.

We estimate one in seven species (14%) are threatened with extinction.

Fishing for meat and oil

Deep-water sharks and rays are in a group of marine vertebrates that are most sensitive to overexploitation. This is because of their long lifespans (possibly up to 450 years for the Greenland shark, Somniosus microcephalus) and low reproduction rate (only 12 pups in a lifetime for the gulper shark, Centrophorus granulosus).

These biological characteristics make them similar to formerly exploited, and now highly protected, marine mammals.

Wikimedia Comons/Hemming1952, CC BY-SA

The Greenland shark and the leafscale gulper shark (Centrophorus squamosus), for example, have population growth rates comparable to the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) and the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), respectively. Despite their known inherent vulnerability, there are very few species-specific management actions for deep-water sharks.

Our research shows that overfishing is the primary threat to deep-water sharks and rays. They are used for their meat and liver oil, which drives targeted fisheries but also incidental capture, meaning any accidental catches are retained by fisheries targeting other species.

In many nations, deep-water sharks and rays are regarded as a welcome catch because of the high value of their liver oil and high demand for skate meat. These are not new trades, but the global expansion and diversification of use, particularly for shark liver oil, is a relatively new phenomenon.

NOAA, CC BY-SA

Targeted shark liver oil fisheries are boom-and-bust fisheries. They drive shark populations down and raise the extinction risk over short periods of time (less than 20 years). There is particular interest in shark liver oil for applications in cosmetics and human health products, including vaccine adjuvants.

This is despite a lack of evaluation of possible human health risks of using liver oil for medical purposes (deep-water sharks can bioaccumulate heavy metals and contaminants at concentrations at or above regulatory thresholds).

Need for global deep-water shark action

There have been tremendous triumphs in shark conservation, including the regulation of the global trade in fins from threatened coastal and pelagic species. But deep-water sharks have been largely left out of conservation discussions.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora has yet to see a listing proposal for a deep-water shark or ray.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

We call for trade and fishing regulations specific to deep-water sharks and rays to ensure legal, traceable and sustainable trade and to prevent their further endangerment.

There are presently limited ways of determining which species comprise internationally traded liver oil. It may be a byproduct of sustainable fisheries but the current lack of regulations could also be masking the trade of threatened species.

We also propose closures of areas important to deep-water sharks and rays to provide refuge from fishing and promote recovery and long-term survival. Nearly every deep-water shark is threatened by incidental capture.

Retention bans have been implemented in some regions as a mitigation strategy, including European waters managed under the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. But they don’t prevent the mortality of prohibited species that are released after being brought to the surface from great depths.

We need efforts to prevent capture in the first place. There is now a global push to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030 through the Convention on Biological Diversity, which New Zealand has ratified.

Our work shows protecting 30% of the deep ocean (200-2000m) would provide around 80% of deep-water shark species with at least partial spatial protection across their range. If a worldwide prohibition of fishing below 800m were to be implemented, it would provide 30% vertical refuge for one third of threatened deep-water sharks and rays.

Even though the extinction risk for these species is much lower than that of their shallow-water relatives, their potential for recovery from overexploitation is much reduced because of their long lifespans and low fecundity. One study estimated it would take 63 years or more for the little gulper shark (Centrophorus uyato) to recover to just 20% of its original population size.

We know many shark populations around the world are in trouble. Threatened deep-water sharks have little chance of recovery without immediate action. Now is the time to implement effective conservation actions in the deep ocean to ensure half of the world’s sharks and rays have a refuge from the global extinction crisis.![]()

Brittany Finucci, Fisheries Scientist, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and Cassandra Rigby, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.