Photo by Sebastian Pena Lambarri on Unsplash

By Mark John Costello, Nord University

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have been used as a conservation measure for decades, but critics continue to argue that evidence of their economic benefits is weak, particularly with regard to fisheries.

Given the challenges in establishing MPAs, including objections from fisheries and the frequently small size and sub-optimal location of protected areas, one would expect their economic benefits to be hard to detect.

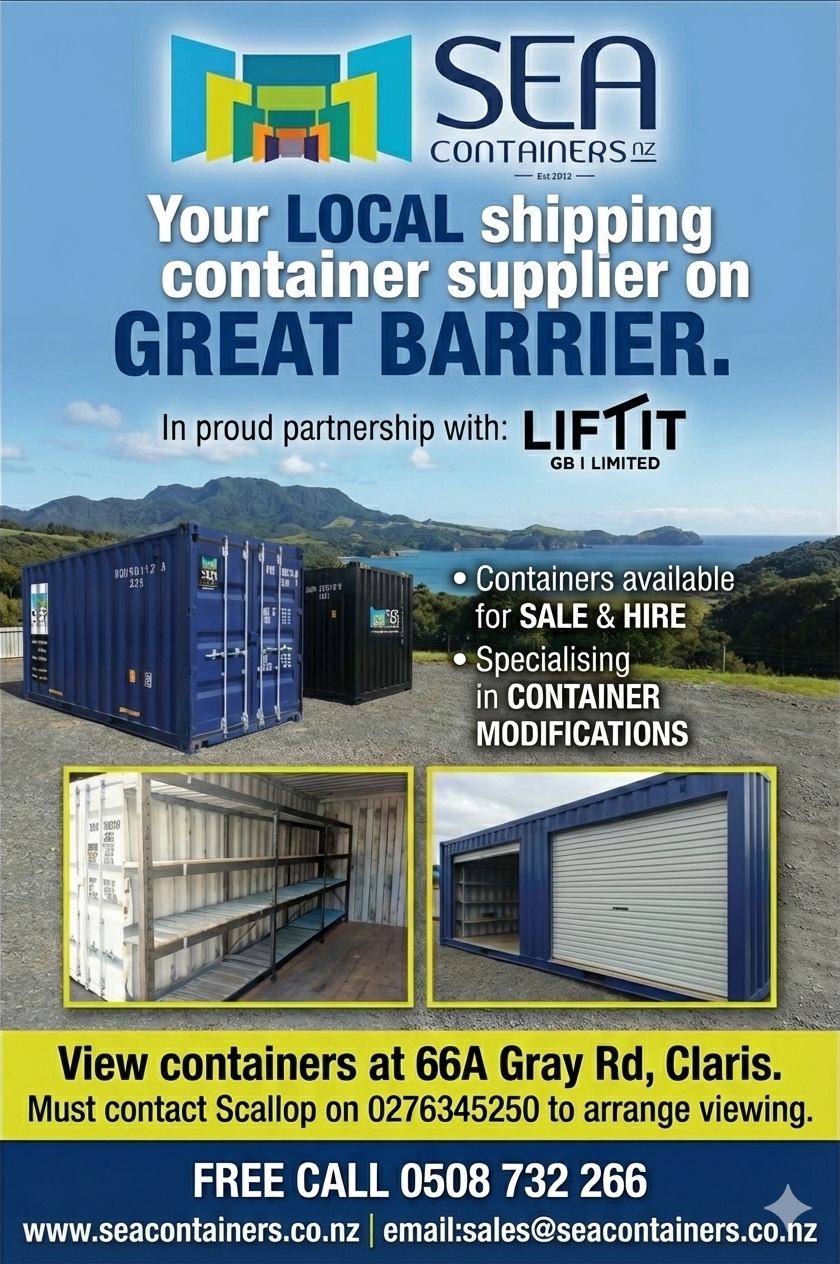

My new study reviews 81 publications about MPAs in 37 countries. It shows their establishment has resulted in benefits to commercial fisheries in 25 countries and to tourism in 24. These benefits covered a diversity of ecosystems, including coral reefs, kelp forests, mangroves, rocky reefs, salt marshes, mudflats and sandy seabed habitats.

Shutterstock/Andrew b Stowe

There were 46 examples of economic benefits to fisheries adjacent to a marine protected area. These include increased fish stocks and catch volumes, higher reproduction and larval “spillover” to fisheries outside the MPA. Other studies also reported larger fish and lobsters close to existing MPAs.

Despite claims in the research literature of fishery displacement due to the establishment of an MPA, it seems the benefits outweigh any temporary disruption of fishing activities.

In my research, I have found no evidence of net costs of an MPA to fisheries anywhere, at any time.

Fishery models need to account for protection benefits

Most economic models estimating the costs marine protected areas impose on fisheries don’t account for the present costs of fishery management (or absence of management).

When an entire fishery is closed temporarily by fishery management, the models estimate the potential benefit from stock recovery. But they don’t do that when a fraction of a fishery is closed for the long-term in an MPA.

Overall, my research shows that MPAs which ban all fishing have lower management costs and greater ecological and fishery benefits than more complex fishery regulations within a protected area. Thus, the economic models of the effects of MPAs need radical revision.

Although it may seem counterintuitive that a full restriction of fishing in an area will result in more fish elsewhere, this happens because MPAs act like a reservoir to replenish adjacent fisheries.

Author provided, CC BY-SA

In financial terms, the capital is invested and people benefit from the interest on the investment. To count the establishment of an MPA as a cost to fisheries is like claiming that interest earned on money is a cost.

In some areas, fishery controls such as quota and the type of gear allowed already restrict fishing over larger areas than a MPA (especially when most MPAs still allow some fishing).

An analysis of the long-term effects of marine reserves in Sweden found they complemented fishery management measures. But when they were reopened to fisheries, even if temporarily, the benefits were promptly lost.

MPAs represent a simple, viable, low-tech and cost-effective strategy that can be used for small and large areas. As such, they have proven highly successful both for safeguarding marine biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. More pertinently, they reverse fishery declines, secure food and ecosystem services and enable the sustainable exploitation of marine resources.

MPAs shift the management of fisheries from being purely a commercial commodity to include the wider socio-economic benefits they provide to coastal communities. This includes food security, cultural activities and sustainable likelihoods. A recent review of 118 studies found that no-take, well enforced and older MPAs most benefited human wellbeing.

Getty Images/Ullstein Bild

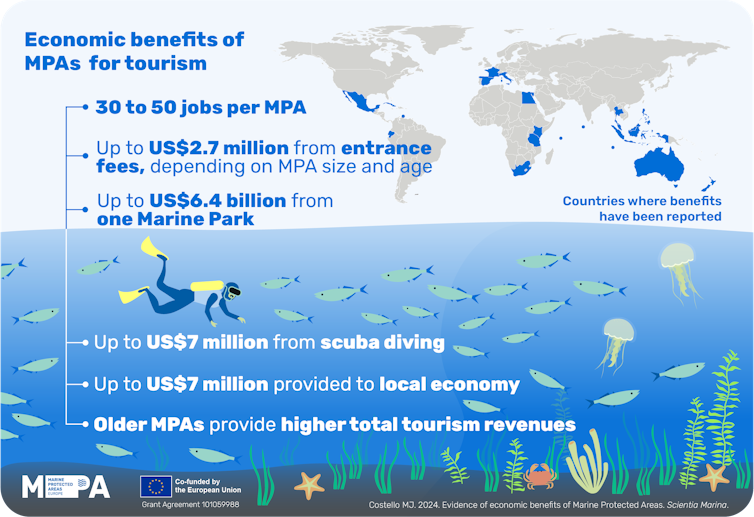

MPAs can generate billions from ecotourism

In addition to economic benefits to fisheries, MPAs that are accessible to the public, and which harbour biologically diverse habitats, can generate millions to billions of dollars in tourism revenue per year.

This revenue is generated not only from entrance fees and MPA-associated businesses that may develop, but also from providing jobs and therefore improving the local economy and living standards, while contributing significantly to national GDP.

The largest benefits to fisheries and biodiversity, and lowest costs in management, come from the designation of MPAs from which no marine wildlife can be killed or removed.

This principle has been termed Ballantine’s Law after the late New Zealand marine biologist Bill Ballantine, known as the “father of marine reserves”.

Author provided, CC BY-SA

Back in the 1970s, Ballantine championed what was then a radical idea – that MPAs should be entirely no-take, permanent areas called marine reserves. This led to the establishment of New Zealand’s first marine reserve.

I have worked with Ballantine and one of our earlier studies found three-quarters of coastal countries didn’t have even one marine reserve. Today, less than 3% of the global ocean is under some form of protection.

Considering the proven benefits and popularity of MPAs, this is a missed opportunity for these countries’ economies and public engagement with nature. Once people witness the benefits of a fully protected area they are likely to want more.

Shutterstock/Bill Xu

The fishing industry and fishing communities have much to gain from MPAs. But outdated misconceptions perpetuated in the scientific literature create barriers to their implementation.

A recent global analysis has prioritised where to locate MPAs to meet the pledge to fully protect at least 30% of ocean habitats by 2030. This goal is supported by the Convention on Biological Diversity, UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Fishery scientists and fishermen need to promote the placement of MPAs as a strategy to support biodiversity, including ecosystem-based management of fisheries. They should work with conservation scientists to realise the true capacity of MPAs for economic success.

Marine protected areas represent our best strategy to reverse declining biodiversity and fisheries, because business-as-usual for global fisheries is unsustainable.![]()

Mark John Costello, Professor, Faculty of Biosciences and Aquaculture, Nord University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.