Halo’s Conor Haughton with an ATV full of standard mustelid traps Photo / Supplied

By Cosmo Kentish-Barnes, RNZ Country File

A pilot using artificial technology to differentiate predators from native birds could be a game-changer for pest control.

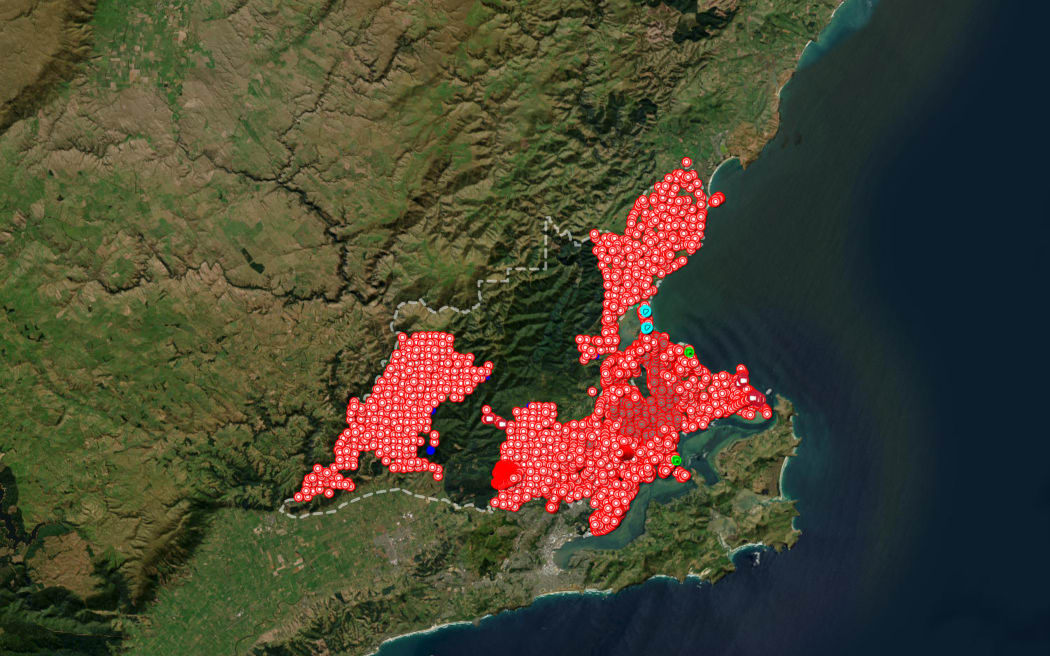

More than 4000 pest control traps have been set as part of the Halo Project, which protects wildlife and habitat around the Orokonui Ecosanctuary in Otago by controlling possums, weasels, stoats and rats.

Now a new trap system driven by artificial intelligence is being rolled out as a pilot, with about 100 such AI traps already on the ground.

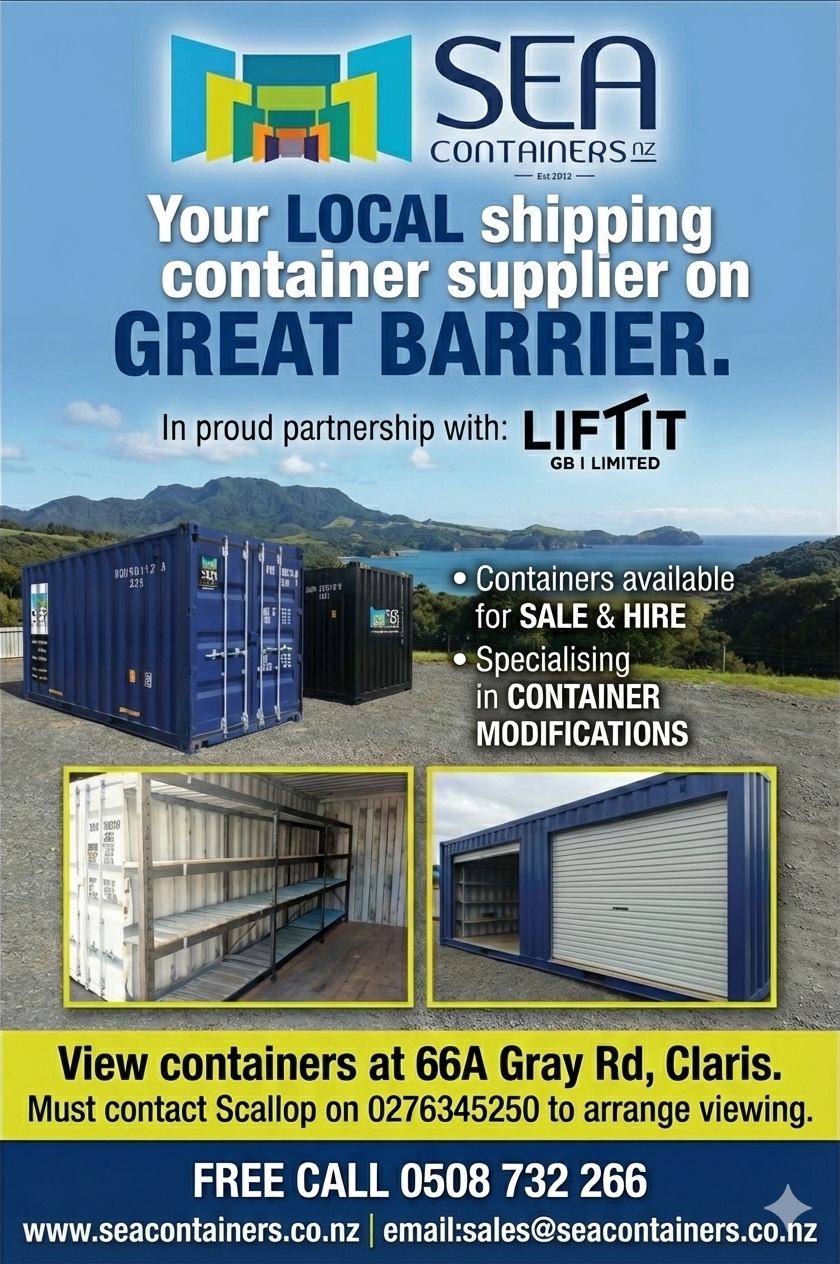

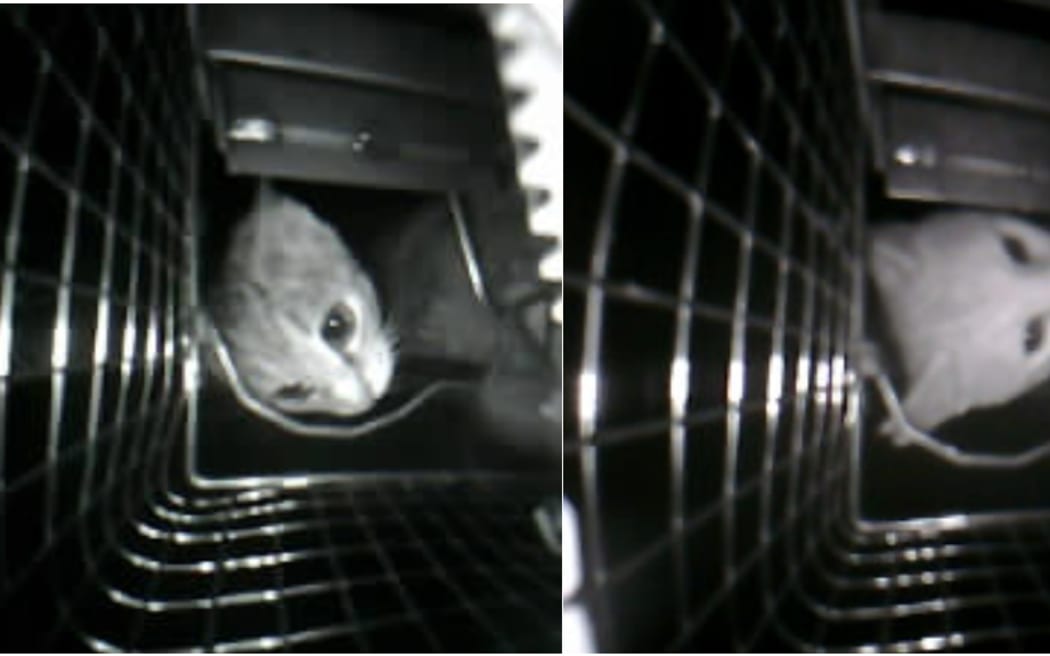

When an animal or bird approaches a trap, a camera takes a series of images which the AI model then assigns a probability score of being a target species.

If an image probability score is greater than a specified threshold (trappers are still working on what value to set the threshold), then the trap will be ‘armed’ or be able to be triggered.

An AI-powered pest control trap Photo / Supplied

The AI model is being trained to spot predators, while leaving indigenous animals or domestic pets alone.

“The ability for these traps to lock out and not activate when there’s something that we don’t want it to catch is pretty remarkable technology,” Halo’s project manager Rhys Millar says.

The Halo Project started in 2013 with a host of local landowners and conservationists getting together.

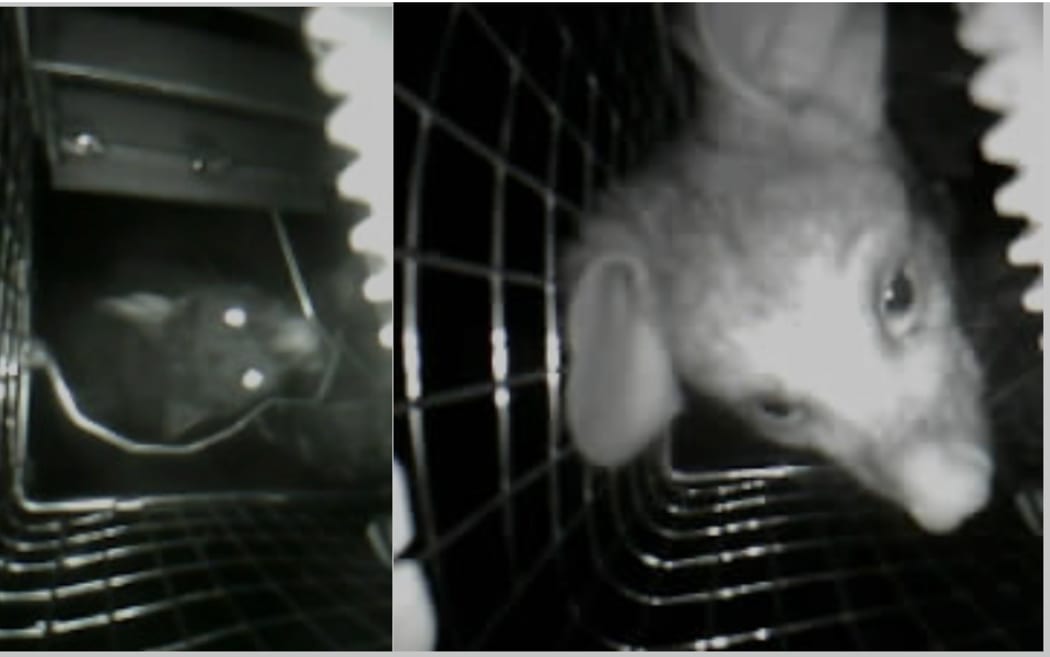

An image of a possum looking into the trap Photo / Supplied

They were concerned that land around the 300-hectare Orokonui Ecosanctuary was being overrun with possums, mustelids and predators.

“If we want the beauty of Orokonui to expand beyond the fence, then we needed to do something about enhancing the rest of that landscape,” Millar says.

Since then, more than 70 landowners have joined the predator-free programme.

An image of a cat looking into the trap Photo / Supplied

It now reaches across 55,000 hectares of land north of Dunedin City.

Running alongside predator-free work is the Source to Sea initiative, which is focussed on restoring waterways, wetlands and forest habitat in Coastal Otago, from West Harbour-Mount Cargill to the Waikouaiti River.

Thanks to local volunteers, about 240,000 plants have gone into the ground so far.

Predator Free operations field lead Kim Miller installs a Gateway system for the AI traps Photo: Supplied

Many were grown at the Project’s own native nursery, which is based in a disused yard on farmer John Chapman’s property.

Chapman also runs a pest trap line for the Halo Project and says native bird species are slowly returning to the area.

“I was quite chuffed the other day, I was walking through the other side of the farm and I saw a bush robin (toutouwai) on the track and that’s the first bush robin I’ve ever seen on this farm in my lifetime.”

A map of the Predator Free trap network Photo / Supplied

Further down the valley is a 9-hectare DOC nature reserve at Long Beach near Whareakeake, where 40,000 native seedlings have been planted.

The Halo Project Source to Sea manager Alice Macklow says it has been awesome to see the community involved.

“We’ve had people from all walks of life, school children, community groups and businesses, we’ve had about 1100 volunteers contribute.”

The fence that goes around the Orokonui Ecosanctuary Photo / Cosmo Kentish-Barnes

The species planted have been carefully matched to suit the environment too, she says.

“So kōtukutuku which is fuchsia, naio and veronica elliptica which is shore hebe, and other plants like harakeke and cabbage tree/ī kōuka.”

Despite the Halo Project’s success, securing funding is becoming increasingly challenging, Millar says.

Up until now, the majority of the funding has come from the Otago Regional Council, Dunedin City Council and Predator Free 2050.

“We are currently working with some corporates to see if we can obtain some ongoing support, but it probably won’t be at the same scale that we have had.”

Sheep farmer John Chapman and Hugh Lindsay at the Halo Project nursery Photo / Cosmo Kentish-Barnes

Taieri Tramping Club Volunteers at Warauwerawera Wharewerawera / Long Beach Photo / Supplied

Source to Sea manager Alice Macklow Photo / Cosmo Kentish-Barnes

Drone shot of planting at Volunteers at Warauwerawera Wharewerawera / Long Beach Photo / Supplied

Another Source to Sea planting site Photo / Supplied

Predator free manager Jonah Kitto-Verhoef with Kim Miller, Alice Macklow and Rhys Millar Photo / Cosmo Kentish-Barnes

The Halo Project HQ near Port Chalmers Photo / Supplied

-RNZ