A high-profile effort to bring back the extinct South Island giant moa is drawing sharp responses from scientists and conservationists, despite backing from Ngāi Tahu and international biotech giant Colossal Biosciences. While some see the project as a moonshot moment for science and Māori-led ecological healing, others warn it’s closer to a Jurassic Park sideshow than serious conservation.

The initiative is backed by Colossal, the Texas-based company behind the so-called “de-extinction” of the woolly mammoth and dire wolf, and involves filmmaker Sir Peter Jackson, the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, and Canterbury Museum. The team says they are reconstructing the moa genome from preserved remains and plan to eventually reintroduce the birds into “expansive, secure ecological reserves.”

Ngāi Tahu appears to support the effort. As Colossal’s announcement puts it: “The South Island giant moa, a species sacred to the Māori and integral to New Zealand’s ecosystem, is a compelling candidate for de-extinction, with unique potential to re-balance native biodiversity.”

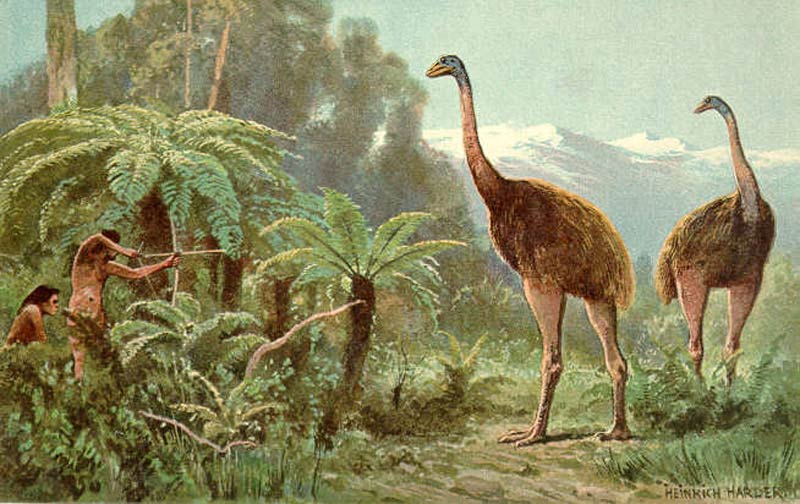

The Bird That Once Was

The South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus) was a flightless bird that once towered up to 3.6 metres tall and weighed over 200 kilograms. But within two centuries of Māori arrival, all nine moa species were gone. The extinction is widely attributed to overhunting. Habitat loss and pākehā-introduced predators followed.

Now, nearly 600 years later, a synthetic version of the moa may be on its way back.

Yet, experts across the motu are voicing concerns—scientific, ethical, cultural, and environmental.

“It Cannot Be a Moa”

Noted wildlife expert Professor Emeritus Philip Seddon of Otago University minced no words. “Any end result will not, cannot be, a moa – a unique treasure created through millennia of adaptation and change. Moa are extinct. Genetic tinkering with the fundamental features of a different life force will not bring moa back.”

Seddon likened the likely outcome to Colossal’s much-publicised “resurrection” of the dire wolf—now acknowledged as a genetically modified grey wolf. “There is no hint in their press release that the best we can hope for is an ecological replacement,” he said.

DNA Offshore, Ethics in Question

Associate Professor Nic Rawlence, Director of Otago’s Palaeogenetics Lab, was equally blunt.

“I’m shocked by this announcement… There is very little support for de-extinction of New Zealand species for many reasons,” Rawlence claimed. He also cited a decade of consultation with iwi, hapū, and rūnanga—but given the public support of Ngāi Tahu, whose research centre is at the heart of the moa project, it is unclear whether he was claiming to represent the views of a specific iwi or hapū. Ngāi Tahu represents the vast majority of the South Island, with the exception of a small section at the top of Te Waipounamu.

While speaking to Predator Free 2050 Professor Rawlence also appeared to make a perhaps jarring and bizarre analogy to European Royalty.

“There’s no habitat left. If you do bring a species back, you need to bring back enough individuals that they are not inbred like the English royal family or the Habsburg dynasty.” he said.

A Moa in Name Only?

The project has also drawn fire for its scientific feasibility. As Professor Amanda Black of Lincoln University put it:

“We don’t have moa eggs, we don’t have good moa genomes, and likely never will. We don’t have a close relative that we could even use as a surrogate.”

She described the project as “technically impossible,” and argued that “it is unethical to bring species back when we haven’t even found ways to save the species we still have.”

Professor Black is also a founding member of Te Tira Whakamātaki, whose 2023 survey of Māori attitudes found that most participants opposed de-extinction, citing habitat degradation, funding priorities, and ecological disconnection, although the report didn’t break down opinion by rohe (region).

“It’s a wasted effort for something that won’t be sustainable… We’ve got kākāpō and stuff that need the attention.” she told Predator Free 2050.

Even the definition of “moa” is under fire, with researchers questioning what to call it if, like the dire wolf, the bird turns out to be a gene-edited emu or rhea.

With Peter Jackson’s involvement and the inevitable comparisons to Jurassic Park, researchers argue that the project raises a fundamental question: is this an act of ecological redemption, or New Zealand’s entry into the entertainment–biology complex?

The researchers behind the survey said the consensus across the entire country was clear: “If the trade-off is between bringing back one extinct species or saving 23 species currently on the brink of extinction, the public said: prioritise the living.”