Coral Holroyd (née Eyre) provides a captivating look into early life on Great Barrier Island, recounting the Eyre family’s experiences from the 1920s. Her story highlights the challenges of pioneering life, community development, and the impact of wartime on the island. Republished with permission from the Kay Stowell archive, this piece preserves and shares valuable historical memories with the Great Barrier Island community.

Māori called it Aotea, Captain Cook named it Barrier Isles but it is commonly known as Great Barrier Island. Tourist brochures promote it as the way New Zealand used to be – it is remote, rugged, with spectacular scenery, unspoilt beaches, hot pools, historic sites and abundant wildlife. The Eyre family lived on the island for over 30 years with a member, Mrs Coral Holroyd, having special memories of early life at Tryphena during the 1930s and 1940s. Her story follows.

After being encouraged by a friend to record her memories, Coral Holroyd (nee Eyre) offers her personal impressions of family life on Great Barrier Island from the 1920s. Her father had purchased a property at Tryphena and as county clerk was involved with much of the development and through his initiatives and skill as a carpenter, built many of the facilities that made life a little easier…

My father, Cyril Fordham Eyre, had been interested in boats from a very early age. On his return from the First World War he decided to buy a property at Tryphena, Great Barrier, with his war gratuity. The safe anchorage in the bay and tidal creek were a boat owner’s delight.

Dad was a tradesman carpenter and these skills were put to good use building the guesthouse which he and his sister Arlie (Isabel) had decided to run. Eight bedrooms, storeroom, maids’ room, dining room with a full-size billiard table and seating for about 20 guests, sitting room, wide verandah and huge kitchen, it must have been about as big as two ordinary houses.

Building was just completed when the Wiltshire was wrecked on Cape Barrier and for some months a constant stream of salvage operators and inspectors stayed there. Isabel became very friendly with one of these officials and later moved to Australia where they were married. Cyril married Ethel Hill in 1926 and about this time a neighbouring property was acquired along with the post office and telephone exchange. The farm was now 1800 acres and as this occupied most of Dad’s time, Mother managed the phone and post office and did all the paperwork connected with the county clerk’s job which my father held until his death in 1951.

During the 1930s Dad’s parents lived on the Barrier. Grandpa was a great gardener and kept us well supplied with fresh vegetables and I can well remember his neat rows (kept straight with a piece of fishing line, of course) of peas and beans, carrots and parsnips. It was a happy time for my sister Joan and I, the houses were a quarter of a mile apart and we used to enjoy visiting Grandma and being spoiled with her delicious cakes and fresh bread.

There was no medical service at the Barrier in those days-everyone travelled to Auckland for medical and dental care. Anyone expecting a baby usually left the island some weeks before the baby was due. How Dad worked-fencing, building, cutting, digging; puriri fence posts and kauri battens to be split, sometimes with the use of gelignite. It was always exciting to us kids to watch the hole being bored with an auger, the gelignite being carefully pushed in and the fuse laid. We were then told to hide well away while the fuse was lit. The subsequent boom, chips flying and smell of gunpowder were more thrilling than any television children watch today.

The stockyards and loading facilities that Dad built were often used when sheep and cattle were shipped to Auckland from the southern part of the island. Sometimes individual farmers sent a load of animals and a stockbuyer, Ellis Jones from Matakana, bought others to ship away. The scow Rahiri came alongside the raceway at high tide, the animals were loaded and she floated off on the next tide. I well remember Jock McKinnon, the skipper, and his booming voice. Cattle were often wild and unused to people, cars and dogs. They were unloaded at Panmure and once one of our bulls charged through a market garden. The Chinese owner was not amused!

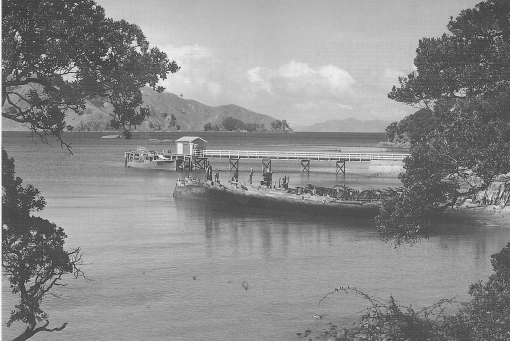

There was a wharf at Shoal Bay, some four to five miles by road and directly opposite our place. The roads were clay and unmetalled so the local steamer would anchor and goods would be winched into dinghies and rowed ashore. Passengers climbed down a rope ladder and jumped into the dinghies’. All this was inconvenient and slow-my father and the five Medland brothers decided to build their own wharf. Kauri trees were felled on our property, pit sawn and dragged out by horse. This was used for the decking. Tea-tree and hardwood piles were driven by a pile-driver and crane built by my father and the hardwood beams came from a derelict vessel bought in Auckland and towed to Tryphena. Later Dad built the Okupu wharf and a number of bridges on the island. Incidentally, I am not sure many people were aware that some extra-wide dressed planks were stored in the wharf shed rafters. These were used for making coffins, once again my father’s skills would be called on when a death occurred.

Until the early 1950s the telephone lines were all connected to a cable which was laid between Tryphena and Port Charles. The line then went to Coromandel. Thames, Auckland. Sometimes the voices were very faint and telephonists had to relay messages-too bad if it was something personal. We had a small switchboard in the house and five or six telephone bells. It was our job to switch callers through when they rang and disconnect them when they had finished-in those days local calls were always three minutes no matter how long they talked. The lines were often damaged in bad weather and Dad would go out to mend the break. It was rough country and sometimes he carried an old-fashioned phone with batteries in a wooden box. At convenient interval she would throw a connecting wire over the line and test ring home to find out where the break was. We didn’t have hours to be open and shut, people were switched through at any time of the day or night. When there was important local news we would give five short rings on each party line and that was the signal for everyone to answer.

During the Second World War a soldier lived with us to ensure that there was someone beside the phone day and night. It was a much sought after job in comparison with the spartan army life. My grandparents had moved to Auckland at the beginning of the war and as their old house was empty the army requisitioned it for a guard post. Seven or eight soldiers lived there and it was their job to patrol the waterfront at night and watch for anything suspicious when the local boats came in. Once, the guard, in full uniform, complete with rifle and bayonet, marched down the wharf watching the loading and unloading not realising the boat was much longer than the wharf, he went right over the end and into the tide. There were plenty of willing hands to help him out.

We had to have a permit to travel back and forth during the war. The soldiers often borrowed our dinghy to go fishing, there was little for them to do on their days off. Sometimes they helped Dad on the farm and often visited Mother for advice on cooking. Tudor Collins, a family friend, was a NZ Herald photographer and part of the crew of a navy patrol boat. When the boat tied up at the wharf on an overnight stop he would arrive at the door with a bundle of photos, always large, which he would wash in our bath. The groceries were delivered by army truck and one day our old horse, Bob, was found with his head in the back of the truck helping himself to loaves of bread.

Schooling was always a problem on the Barrier. When Joan reached school age there were only six children needing a teacher. On making inquiries at the Education Board, Mother was advised they would pay a teacher if she could find one and provide board. Miss Buggy, a retired London teacher, very much of the old school, was chosen. We rode, one behind the other, on old Bob to school. After Miss Buggy retired we were taken by car to Medlands School, five miles away. This did not last long as our new teacher was called up to join the Fleet Air Arm, so Joan and I completed our primary education through the Correspondence School. My father bought a 1931 Chevrolet and despite the shocking state of Barrier roads it kept going for many years. All repairs there were of the do-it-yourself type, from replacing gearboxes to relining brakes.

Many of the roads on the Barrier had been built during the Depression by gangs of relief workers. (One of the workers, Ernie Osborne, managed to gash his leg with an axe. It was a large cut that required stitching; the only person to stitch it up was my mother-and stitch it up she did, with an ordinary needle and thread. It was an experience she used to recall with a shiver afterwards.) The clay roads were later metalled and during the war a road was built from Awana to Okiwi to give access from Port Fitzroy to Tryphena.

The council never seemed to have enough money to do adequate work on the roads-the farms were scattered and rates were low. It was difficult and expensive to collect rates from absentee owners; even though it was an out-of-the-way place every letter of the law had to be obeyed as one resident was a bush lawyer and he watched to see all council business was carried out correctly.

Sometimes we had visits from VIPs-Sir Cyril Newall and Sir Bernard Freyberg both came to the Barrier when they were Governor-General and had lunch in our dining room along with the members of the county council and their wives. We often had Members of Parliament to stay a night or two, including M J Savage. My parents did not agree with his politics but Mother recalled that he was a “jovial little man”.

Mother never ran a guest-house but we seemed to have a steady stream of visitors. Mrs Mclean, the first district nurse, was a good friend and always stayed on her trip through the island. There were Post Office linemen who came to work on the telephones and in summer came the campers. There were no recognised camping grounds then but we were happy to let anyone camp on our property free of charge. Pohutukawa trees surrounded the house and fringed the edges of the many bays. Some of the valleys were filled with tea-tree and the flowers provided nectar for beehives which Ernest Osborne and Johnathan Blackwell kept on our property. We were always given plenty of honey in return and sometimes a full comb as well.

When elections were held in the local school Dad was usually poll clerk and Mother returning officer- people came to vote and staved for a chat. It was the same on “Boat Da)'” when people came to post their mail and wait for the boat to come in. When the bags of mail and bundles of papers were unloaded they were brought to the post office, which was a small room to the side of our house. There Mother and Dad would sort them and put letters and parcels in respective bags. A whole week’s supply of newspapers came at once and as Joan and I became old enough it was our job to undo these bundles and make sure each subscriber had his six Heralds.

Everything you needed came on this weekly boat-petrol in 44-gallon drums, timber, bread, groceries, clothes and household goods sent for by mail order, Christmas and birthday presents. Sometimes the goods had to be sent back and exchanged as they were not suitable or didn’t fit.

Most people only visited Auckland once or twice a year at that time-the journey could be very unpleasant if it was a bad day. Head winds in a slow Northern Company vessel such as the Motu meant six or seven hours of seasickness for some of us. After the war, Strongmans of Coromandel built a more suitable passenger vessel, the Caramel, which was quicker and more comfortable, although we still got seasick!

During the war the Northern Company incorporated the Barrier run into the Tauranga trip. They would bring goods from Auckland to Barrier ports on the way down on a Thursday and then call’ and collect mail, passengers and other goods on a Saturday on the return journey. It was probably done to save fuel and manpower but it was very inconvenient for everyone having to make two trips to meet the boat-especially as it came in the late evening and it was not pleasant turning out on cold, dark, winter nights. Lanterns had to be held high on the wharf to guide the boat in.

My grandparents returned to the Barrier in 1944. Grandpa died there and I remember Dad taking him up to Auckland in our launch for burial. During the war the launch was always kept ready with emergency provisions in case we had to make a quick getaway. We had one or two scares when a Japanese aircraft-carrier or submarine was supposed to have been sighted off the coast. I was about nine or ten and can still feel the tense atmosphere until the scare subsided.

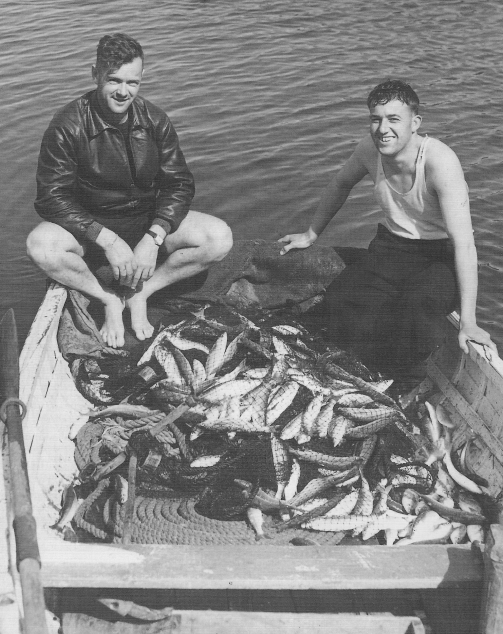

Fishing round the Barrier was always excellent. Dad often rowed out to the reef for an hour or two fishing or to set a crayfish pot. Often on a Sunday we took a picnic and went in the launch to Schooner Bay or Woolshed Bay. As well as fishing there were always planks to pick up off the beach-not driftwood, but rough planks that had been used in the holds of ships as packing. These were very useful around the farm.

Wood ranges, candles and kerosene lamps were the order of the day but we had gas lighting in the main rooms. As well as building the house, Dad had made much of the furniture-carpenters were cabinet-makers as well! There was no factory-made stuff.

My mother had grown up in Cambridge and Auckland and it must have been difficult for her and indeed the other women to learn to bake bread and cook on a coal range. It seems to me the Barrier was one place where the pioneer philosophy of turning your hand to anything was a much-needed one in view of its isolation and lack of services.

New Zealand Memories, Oct 1997. Reproduced with permission.