“A Trip to Great Barrier Island In 1932,” penned by Oliver Pipe, offers a captivating glimpse into a bygone era of adventure and natural wonder on Great Barrier Island. Originally published in the June 1977 issue of the Ohinemuri Regional History Journal, this narrative recounts a rustic camping holiday marked by encounters with native wildlife and the local logging industry. This article has been republished with permission from the Kay Stowell archive, preserving a piece of regional history for contemporary readers.

By Oliver Pipe

From the Ohinemuri Regional History Journal, June 1977

My eldest brother and I decided to have a camping holiday on Great Barrier Island. He was working in the Waitakere Ranges helping to form what is now the Scenic Road, and I was working at the Waikino Battery. When the Christmas holidays arrived, we booked our passage on the old coastal steamer “Claymore” with over 100 other passengers. The “Claymore” was used many years later in the recovery of the “Niagara” gold.

We left Auckland on a fine sunny day, and on our way across, we passed a paddlewheel steamer called the “Lyttelton,” which was headed for Auckland with a raft of kauri logs in tow for the Kauri Timber Co.’s mill, which was on the waterfront at Freeman’s Bay where the present Shell House now stands. These log rafts were made by tying the huge logs together by a chain, passed through a couple of holes augered through the butt end of the logs, and attached to a heavy central chain which ran the full length of the raft. The raft in this instance would have been around 500 to 800 yards long, and right at the back was a small shelter where a man rode and somehow reported to the boat ahead if a log should break loose. In the heyday of the kauri milling, floating logs were a danger to shipping, and were known to have floated as far as Fiji. The miller, or bush contractor, was expected by law to mark his logs with his particular brand, by bruising it into the ends of each log with a special type of branding iron.

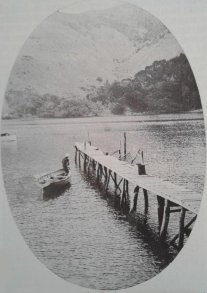

When we were approaching Little Barrier Island, someone sighted a whale, and when everyone went to one side to see it, our boat heeled alarmingly, and we were ordered back by crew members. We called at Port Fitzroy in the north of the Island first, disembarked most of our passengers, a lot of the cargo which included many cases of Big Tree benzine, two four-gallon tins to each case, and also lots of 44-gallon drums. After an hour or two at Fitzroy, we set off for Whangaparapara that was halfway down the Island and the harbor from whence the log raft had been assembled. Logging was in full swing in that area in 1932. It being Christmas, most of the bushmen were headed for Auckland and embarked when we got off. There was quite a settlement of bush houses, and a skeleton crew had remained to keep their eye on things, as there was much valuable equipment in use there.

We erected our very small tent handy to a stream just above the wharf, and went to have a look at the log boom at the head of the harbor. This consisted of a large number of floating kauri logs chained together to form a holding area for the logs which were jacked off the bush trucks and skidded into the water. The floating logs were assembled into the rafts within the booms. Some logs were known as “sinkers” and had to be lashed between two floaters for towing. Our tent site proved to be a dead loss as the mosquitoes drove us mad. We got some relief by wrapping our heads in thin tea towels and burning dry cow manure over an open fire at the tent mouth. I always think of this when I see incense burning. The first morning we were aroused by large detonations and discovered that it was some of the bushmen blasting fish within the boom. We had blasted fish for breakfast most mornings afterwards.

One day we went with one of the bushmen who had remained as a watchman to inspect some of the gear. There was a bush tram which ran from the harbor boom to the foothills, perhaps a mile or two. A stationary log hauler dragged the logs for half a mile down the hill to the skids where they were loaded onto this rail link. There were, I think, six of these steam-driven haulers which were capable of hauling logs a half mile and then by using snatch blocks attached to another growing tree, to haul the logs a half mile away from the hauler. By that method, each hauler could account for one mile of haulage. There was also several miles of a bush tramline, the locomotive being an old tractor on tram wheels. In all, we were told they were dragging logs by combined methods up to 16 miles to the harbor. Some of the snig trenches were twenty feet deep and while traversing one of these, my brother gashed his foot badly. The bushman had no disinfectant, so he pared some plug tobacco into a tin dish, poured boiling water onto it, and said: “Put your foot into it.” It was a very painful cure but effective. Some of the bush houses were built of pit-sawn timber with weatherboards 18″ wide. I often think of the wastage in kauri bush working as only the boles of the trees were extracted and the heads with really huge limbs were left to rot. On our conducted trip into the bush that day, we came upon a nikau roofed shelter where all the huge crosscut saws were reposing in forked sticks with all the teeth sharpened, greased ready to start after the holidays. If my memory serves me right, some of these saws would be ten to twelve feet long. They certainly grew big trees at the Barrier.

One day on a trip from Whangaparapara to Okupu, we passed the remains of an old gold mining battery. Years later the late Mr. James Noble (last battery manager at Waikino) informed me that the battery had been shifted from Owharoa to the Barrier – then to Muirs Reef at Te Puke – and eventually came back to Owharoa and was known as the Golden Dawn. It had originally been named the Rising Sun. At Okupu, the Public Works Department as it was then known had erected miles of fences and laced them with tea tree to try and stop sand drift and had also planted pine. They had started a quarry and were going to build a big aerodrome. A local resident informed us that it was going to be a military aerodrome for the protection of Auckland, but who from we did not know. The War was still seven years off. I often wonder how much was built. We caught sizeable snapper off the wharf and went fishing with local crayfishermen and had a very enjoyable fortnight’s holiday. When we picked up returning holidaymakers on the last day, they invariably had a couple of benzine boxes of hapuka fillets to take home to Auckland or sugar bags of crayfish, and in some cases smoked fish. An old man who lived in a house just above the wharf took us under his wing and had us up for a meal a couple of times. He had an old boat below his section called the “Cobra.” He had built it himself years before and used to sail single-handed to Auckland. He told us that he had once rowed the 65 miles to Auckland. He had pit-sawn the timber and built his house and furniture himself and also played a violin which he had built himself. His name was Osborne, and he would have been 60 or 70 then, and had been born on the Barrier. What a great pity one had not taken more notice of what he told us.