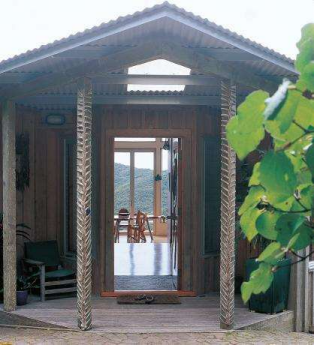

Nikau leaves have been braided around the posts at the front door. The scalloped roof line is visible from the garden. Each locally crafted dining chair is unique. Sue Hoffart meets a Great Barrier resident who has made the most of the island’s special magic.

Writer: Sue Hoffart Photographer: Kevin Emirali

At the south-eastern end of Great Barrier Island, a gravel road passes a “No exit: legal road stops” sign. Judy Gilbert lives beyond the point of no return. The former Auckland city dweller has happily forsaken reticulated power and water along with traffic noise, neighbours, and the need to rush everywhere all the time. Now she’s used to gardening on steep, rocky, wind-ravaged terrain in the company of friendly kaka. And she is unfazed by the need to trap rats, deal with a composting toilet, or wait for her grocery order to arrive by ferry.

This life is, after all, the realisation of a thirty-three-year dream. Judy was just nineteen and a first-year teacher when she bought into a collectively owned 240-hectare block of rugged coastal land on the island in Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf.

Back in those barefoot hippie days, she was drawn to the island’s beauty and alternative lifestyle options. But it wasn’t until she was in her forties and married with a school-age son that the lure of the Barrier finally overwhelmed her. “It was time for a big change,” says Judy. “I was wanting to come and live somewhere very different, to have a lot more space for myself. And I wanted my son to have a taste of rural living.”

So she and husband Scott Macindoe, who has since elected to spend most of the year on the mainland while their son Guy finishes secondary school, drew up a basic floor plan and presented it to Auckland architect Karl Majurey. He built a tiny model of the house with a scallop shell on top to show how the distinctive roof line would look.

“We said to him, ‘Make magic’. And he did. When I saw the scale model, it made me cry; it was so beautiful. And it’s been known as the Scallop House ever since.”

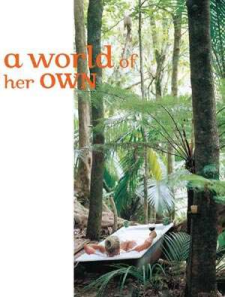

“Home—its situation, style, and contents—is essential to my sense of wellbeing. To be surrounded by natural beauty and drenched in sunlight is really uplifting. Other times I’m completely surrounded in mist for days at a time, and it’s really like being in a world of your own.”

The real thing is even better than she’d hoped, set high amid kanuka and steeply sloping native bush. Deep timber decking offers sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean with Oruawharo Bay and Medlands Beach visible below, and Hirakimata and other peaks forming a dramatic backdrop. Walls are hung with mostly local art, and Barrier wood artist Peter Edmonds created the macrocarpa front door. He modelled the design on the pounamu carving that hangs around Judy’s neck, married it with a stylised unfurling ponga frond, and studded the timber with whole paua shells.

Locals built the house, though building materials had to come from Auckland. But first, a 450-metre driveway had to be hand-cut through the bush, a generator installed, water sourced, and a shed built. The house has solar panels, rainwater storage tanks, a gas hob and oven, and Judy chops and carts firewood to feed her wetback wood stove in winter. “It’s not like town where you hook up to the grid. But when I come home and we’ve had a gorgeous day and my solar batteries are fully charged, it always feels like pennies from heaven to me.”

She feels the same way about storms. After bad weather, she and her girlfriends collect the washed-up seaweed that helps nourish their gardens. “To build a garden here, you have to build soil. If ever you have cars going to town, they come back loaded with sheep pellets and potting mix. It’s hilarious what comes in on the boats and planes. All very practical stuff.”

She has discovered that bougainvillea, canna lilies, vireyas, azaleas, and succulents thrive in the difficult high-acidity soil and withstand periods of abandonment when she is in the city or travelling overseas. Though she battles—and occasionally shoots—rabbits in order to keep a salad garden, Judy happily shares her citrus, figs, plums, bananas, and nectarines with the abundant birdlife. “I don’t care if the birds get all the fruit; I just so enjoy birdwatching.”

The house is headquarters for her Windy Hill – Rosalie Bay Catchment Trust, which aims to regenerate native flora and fauna through pest management. She has created jobs by employing field workers to trap rats and cats and in the process cured her own squeamish attitude to rodents. Other island pleasures include regular yoga classes, dancing with girlfriends, art exhibitions, concerts, and the occasional soak in her sun-dappled bush bath, a gift from a visiting friend.

Despite her obvious passion for the island, the Barrier does not feature in Judy’s long-term residential plans. “My dream for my old age is for all my girlfriends to sell our places and pool our money and buy our own retirement home. We’ll have handsome boys to push us round in our wheelchairs and change our colostomy bags.”

- Reproduced with permission from NZ House & Garden – Subject to copyright in its entirety.