It’s like déjà vu in the world of wheels. The electric vehicle market, is hitting the skids.

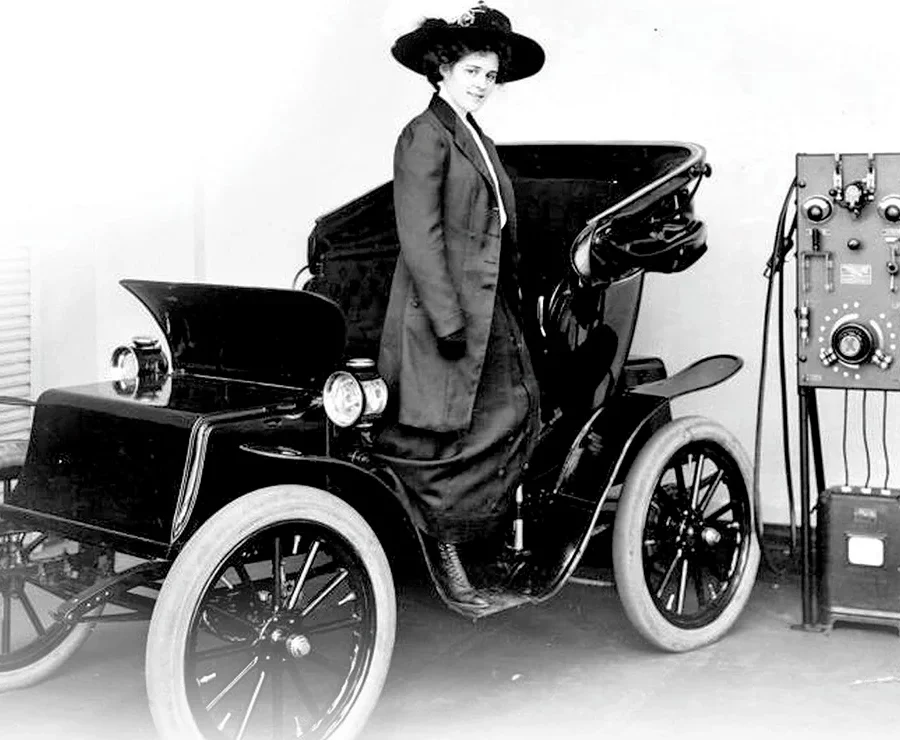

An early-1900s electric automobile with a mercury arc rectifier, once used to charge EVs. Photo / Museum of Innovation and Science

EDITORIAL:

It was 1896 the dawn of motoring, electric cars were the dazzling stars of the automobile universe, celebrated for their hushed whispers and effortless simplicity, especially in the bustling hearts of cities. Icons like Ferdinand Porsche and Thomas Edison explored the realm of electric vehicle (EV) technology. Even Henry Ford, the gasoline vehicle titan, toyed with the idea of joining forces with Edison in the electric car arena. Yet, the allure of gasoline vehicles, epitomized by Ford’s Model T, along with the bonanza of cheap oil, eclipsed the electric vehicle’s early luminescence by the 1930s.

Fast forward to today, and it’s like déjà vu in the world of wheels. The electric vehicle market, is hitting the skids. U.S. dealerships are brimming with EVs – a stark contrast to just a year ago. Models like the Ford F-150 Lightning and Mustang Mach-E are experiencing days on end waiting for buyers. This has led giants like the blue oval and GM to reevaluate their production strategies, hitting the brakes on electric aspirations.

In the second-hand market, the scenario is equally bleak. The value of used EVs has plummeted. An even more alarming bellwether is the freefall in stock values of companies like Rivian since their exuberant market debut in 2021, signaling eroding investor confidence in the EV sector.

So, what’s flattened the EV ecosystem? It appears that EVs are, once again, fading into an unattractive solution to a seemingly distant problem.

Climate change and the specter of high oil prices can largely be attributed for supercharging the hype for EVs in the early 2010s, with demand further juiced up by political incentives. However, in the post-COVID era and in the shadows of Putin’s war on Ukraine, gas prices have deflated, and world leaders have eased off the accelerator on climate reduction targets, opting instead to kick CO2 up another gear, to jump-start economic growth.

EVs. They sort of suck.

Then there’s the elephant in the room – the actual experience of using EVs. Remember the days when spotting a Tesla was about as rare as spotting one of Elon’s exploding rockets? Boy, have those tables turned. Now that more people have driven them, the allure seems to be deflating faster than a punctured tire (oh, the joys of EV tire wear – just another one of those undisclosed perks you’ll need to get used to).

For about 15 years, the EV dream has been peddled not only as a planet-saver but also as a no-compromise future. Now we’re actually getting to experience the unvarnished truth, and it’s anything but.

Early on, we were promised leaps and bounds in battery technology that would increase range and demolish charge time. The reality is in some ways, the opposite. Today’s EVs primarily rely on lithium-ion batteries, a technology dating back to the laptops of the 1990s. In fact Tesla’s recent pivot to Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries, while dropping the cost of the EV itself, has paradoxically ultimately curtailed the car’s range and increased charge time.

Charging infrastructure, the lifeblood of EVs, is also riddled with inadequacies. A recent investigation by The Wall Street Journal revealed that up to a third of non-Tesla chargers across the U.S. were inoperable. Should you miraculously find a functional charger, sans a daunting queue, the process is anything but swift. Charging an EV from 20% to 80%, even with the latest tech, still takes around 45 minutes on average, a far cry from the ‘no-compromise, super-fast charging’ utopia fan boy tech journalists promised us for more than a decade (usually by citing futuristic battery tech which almost never makes it to market). Musk has of course been guilty of selling these dreams too.

Here for a good time, not a long time

As humans, there’s a tipping point in altruism where we tolerate inconvenience for the greater good. But it seems that whittling away hours at a charging station to add less than seconds to the life of the planet, at some point in the future, just isn’t a fox many are willing to hunt.

In a strategic, perhaps largely unforeseen pivot, Tesla is opening its supercharger network to rivals like Ford and Rivian. This is far from a charitable gesture, rather a more calculated gambit. Tesla, you’ll rememeber was once poised to be the Toyota of the overall car industry. If the nightmare of charging an EV continues, it risks being the leader of an EV-only niche. To be honest, this feels like a move to shift public perception and make the EV sector seem like a worthwhile proposition for the consumer, in a category of diminishing returns.

Politically Charged – It’s industry and ICE

Part of that diminishing return can be attributed to a post-COVID political environment which has undergone seismic shifts. Countries like the UK and New Zealand are actually reversing course on EV incentives, even implementing new road user charges for electric vehicles, marking a dramatic volte-face from their earlier pro-EV stance.

This pivot isn’t necessarily a nod to fossil fuel interests, but also a recognition that in a world where heavy hitters like China, the U.S., and India continue to belch CO2, meaningful emission reductions by a group of tiny do-good nations is, to put it frankly, a pipe dream.

Today’s politicians, it seems, would rather turn the key on (albeit polluting) industry and cheap ICE vehicles, to get (or keep) cash in the bank, for tackling climate in the future. The alternative, they seem to think, is to wind down industry at home, only for it to belch out somewhere overseas.

Those with a keen eye can observe this in action. Climate change discussions these days seem to be the purview of ex-prime ministers and the like, at gatherings like Davos and COP28, rather than a widespread, urgent discourse.

Public resignation and an industry that will have to sustain itself

As extreme weather events ravage the world, the public sentiment is one of resignation, left to endure the aftermath of climate changes. The general view is that the financial burden of climate change should fall on the shoulders of wealthy industry magnates who’ve profited from emissions. These same emitters are busy threatening politicians they’ll down tools and leave their countries, if they’re forced to foot the bill.

It seems, then, that the future of the electric car, and indeed green energy itself, will be largely shaped by the very companies that stand to gain the most. Tesla is rallying around its contemporaries as governments take a back seat, but whether this will be enough to supercharge the sector remains to be seen.

EVs thereby find themselves at another crossroads, eerily echoing their past. They faltered in the early 20th century when gasoline took the lead. Today, the modern parallel to the Model T is the Toyota Hybrid, a symbol of practical and accessible green technology. The critical question is whether the electric car will repeat its historical cycle of boom and bust, or will it, this time, steer us towards a more sustainable, green future?

This content may be redistributed on your platform, including websites and print, with attribution to AoteaGBI.news – The Barrier Independent.